Orchestras continue to innovate and entertain despite lack of government support

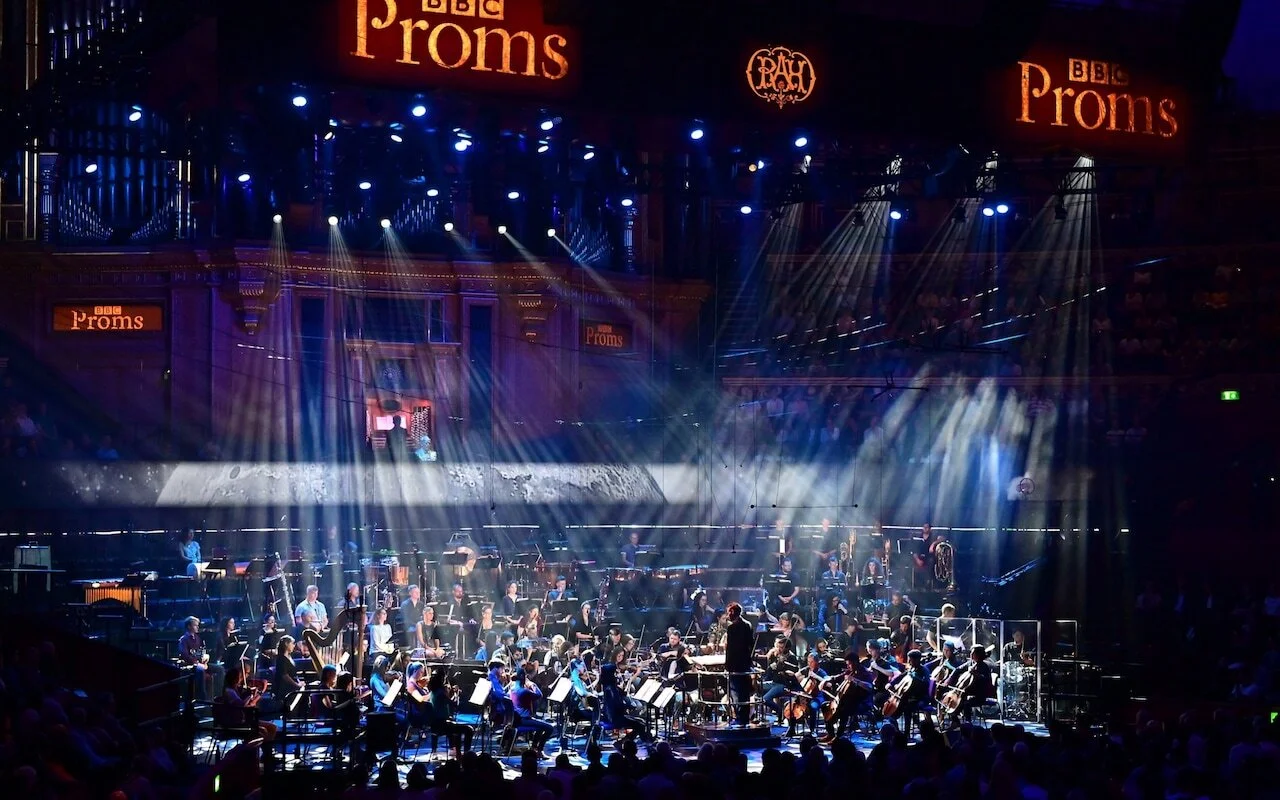

The BBC Proms in 2019. (Photo Credit: Mark Allan / BBC)

Our Orchestras‘ only hope: how technology can fuse our splintered musicians together again

By Izzie Price

The Daily Telegraph

September 30, 2020

Orchestras are symbiotic by nature – social distancing would alter their very core. But, finds Izzie Price, technology may well save the day.

“After two minutes of sound checking, the orchestra began to play. Eighty people with common purpose, creating art despite all the obstacles. Our building was alive again.”

This is how Julian Hepple, Head of Recording & Audio Visual at Guildhall School of Music and Drama, describes the power of the school’s low latency system: a technological feat that allows orchestras to play together as one, and a much-needed resource after COVID-19 plunged said orchestras into silence.

“I was on the Rob Brydon UK tour when [lockdown] happened...I’ll never forget [the] moment we went home during the sound check in Guildford,” says freelance cellist Gabriella Swallow. “Overnight, a year’s worth of work evaporated.”

What followed was a period of grief, fear and frustration for the country’s creative industries – and for orchestras, there were very real concerns that the orchestral landscape may never return to normal. Sir Mark Elder and Sir Simon Rattle – two of the UK’s foremost and most revered conductors – wrote an open letter expressing with unflinching urgency the perilous future faced by the country’s orchestras. “There’s a real possibility of a devastated landscape on the other side of this; orchestras may not survive, and if they do, they may face insuperable obstacles to remain solvent in our new reality,” they wrote.

When the government announced its £1.57 billion rescue package for the UK’s creative industries, this was welcomed by senior figures across Britain’s creative landscape. “It has been a very welcome and substantial investment and recognition by the Government of the particular challenges that the cultural sectors face,” says Michael Eakin, Chief Executive of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. “It will help the sector get through to the end of the financial year, in March 2021. However there will remain a challenge of recovery through 2021 and beyond for many organizations, especially if restrictions continue well into next year.”

The arts is on borrowed time and is still hanging by a thread. And for orchestras, there still remains the question of how to navigate social distancing restrictions in order to continue playing as one.

After all, playing together in harmony – remaining hyper-sensitive to every note played by all the other musicians, working together under the omnipotent guide that is the conductor’s baton – is an orchestra’s bread and butter. Orchestras, by their very nature, are symbiotic. They’re not designed to be split into singular, disparate entities (entities that are doubtless exceptionally talented musicians nonetheless). They’re a living, breathing force; a single unit, working together to bring a piece of music to life.

But Covid-19, alas, is also a living, breathing force that just this week has resulted in new restrictions and growing fears of a second lockdown. So how can orchestras continue to come together to produce the exquisite symphonious music that is cherished by so many?

This is a question that Guildhall, for one, can proffer a technological answer to, “For musicians to perform "in sync" you need a latency (the delay between you speaking, and someone else hearing) to be as close to real life as possible,” explains Julian Hepple. “On a Zoom call the latency can be as long as 1/2 a second. We can move very high-quality audio and video from any point in the buildings to another in 6/1000's of a second – allowing our musicians to perform together despite the physical distance.”

First implemented for the school’s premier music prize, the Gold Medal, and its corresponding concert, the low latency system allows for the orchestra to be split between four different performance spaces, and still play together as one. “There was something totally mind blowing about hearing the low latency system for the first time,” says Vice Principal & Director of Music Jonathan Vaughan. “The idea that the conductor in another room can actually hear the timpani sooner than they would in a live hall (due to the distance) just leaves me slack jawed in wonder.” The City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO), too, has orchestrated innovative ways of playing together whilst adhering to the restrictions.

“We did a special concert from a warehouse in Birmingham on 5 September, 100 years to the day

since the orchestra’s very first concert,” says Stephen Maddock, Chief Executive of the CBSO. “All players had their temperatures checked every day, wore face coverings at all times when moving around the building, and sat at [a] two meter distance from each other.” This two meter distancing system was – needless to say – not an ideal means of making music together, and the process was difficult for the performers. “With the largest orchestra assembled in the UK since March – around 75 players – this was very challenging in terms of hearing each other and coordination. But we did it.” This performance was filmed, and is available for free until 30 September on YouTube and Vimeo.

Another orchestra that has managed to play together – with precautions similar to that of the CBSO – is the Academy of St Martin in the Fields. “As we first started playing the Grainger orchestration of ‘Danny Boy’ at the ASMF sessions I had to work hard to hold back tears,” says Principal Horn Stephen Stirling, in reference to a video recording session at Blackheath Halls. “It was the first work I left the house for after lockdown and I doubt I’ll ever forget it.”

Evidently, then, there are orchestras who are successfully navigating the restrictions to continue playing together for the present – something that means the world to the performers and creatives involved. But what does the future hold for orchestral music? Will it be excessively reliant on tech in order to perform for audiences? Or is there hope for live performances to return to our stages once again?

Well, as far as the future of orchestras is concerned, technology is certainly not without merit. Clod Ensemble, for one, is working to encourage more young people into the music sector through its Ear Opener project: a digital series of lessons teaching students how to compose their own music. “The number [of students] studying A Level music have dropped 32% in six years – we had an educational crisis before we had a public health crisis,” says Co-Artistic Director Paul Clark. “But the classroom isn’t always the best place to think about music - so I’m looking forward to seeing how educators rise to the challenge of creating online content and new ways of learning.” Presumably, then, this educational initiative is doing its part to safeguard the future of our orchestras through inspiring young people to continue considering careers in the music industry, despite its precarious fragility just now.

Regarding live performances, though, there is a cacophonous agreement within the classical music industry to return orchestras to the stage – with audiences sitting front row. “[It’s] clear that many people have loved being able to watch concerts from their home, and whilst uncertainty ensues around live performances, it is wonderful to have this alternative way to engage with live music making,” says Ellie Carnegie-Brown, Executive Producer at The Multi Story Orchestra.

“[But] digital performances could never replace live performance...music making is all about performing with other people, and recording your part in isolation is actually very difficult and not much fun. [Furthermore], human interaction and ‘unedited’ sound and performance is so much of what makes going to a concert special.”

Ellie’s sentiment is echoed - with redoubled and deeply significant concerns – by Baluji Shrivastav OBE, Musical Director of Inner Vision Orchestra: the UK’s only blind professional orchestra. “We are blind musicians who depend on listening to each other even more than sighted musicians, who read music while they are playing,” he explains. “Unless we are physically together we cannot function fully.”

Baluji speaks with deep emotion about what performing in front of a live audience means for Inner Vision. “When we perform in front of a live audience, our blindness is irrelevant to us. The interaction with the audience makes us complete, and adds a dimension to the music and the experience because music is about communication and we need to feel that. That is our life blood.”

If one thing’s for sure, then, it’s that there’s hope. Stephen Maddock is planning on starting orchestral concerts with the CBSO later in the autumn: “Even if we have to have a smaller orchestra (we think we can fit 50-60 musicians on stage at [a] two meter distance, down from our normal 90-100) and much smaller audiences (at two meter distancing, seating capacity is around 25 per cent of the usual size) we are determined to start producing art again,” he says. Second lockdown permitting, here’s hoping other orchestras are able to look at following suit.

And there’s hope for the present, too. “Nothing will beat the wonder of hearing a symphony orchestra together in a space, but while we can't do that, we'll work tirelessly with our technological systems to create alternative ways of sharing musical expression,” says Julian Hepple. “I think Victor Hugo hit the nail right on the head when he said: ‘Music expresses that which cannot be said and on which it is impossible to be silent.’ Personally, I need quite a large slice of that right now.”

To read the full article, click here.